Вавада Казино - Регистрация и Вход на Vavada

Vavada Casino - платформа с азартными играми, основанная в 2017 году. Заведение привлекает своим удобством и классическим оформлением. Функционал многообразен, а навигация крайне проста. Пользователи могут создать аккаунт в несколько кликов, пополнить счет через 32 платежных системы, в считанные минуты найти интересующий их релиз. Весь софт, а это более 5000 онлайн машин, распределен по категориям: столы, live, слоты. Для удобства сортировки созданы фильтры “Hit”, “New” и по провайдерам. Практически во всех развлечениях представлен бесплатный режим.

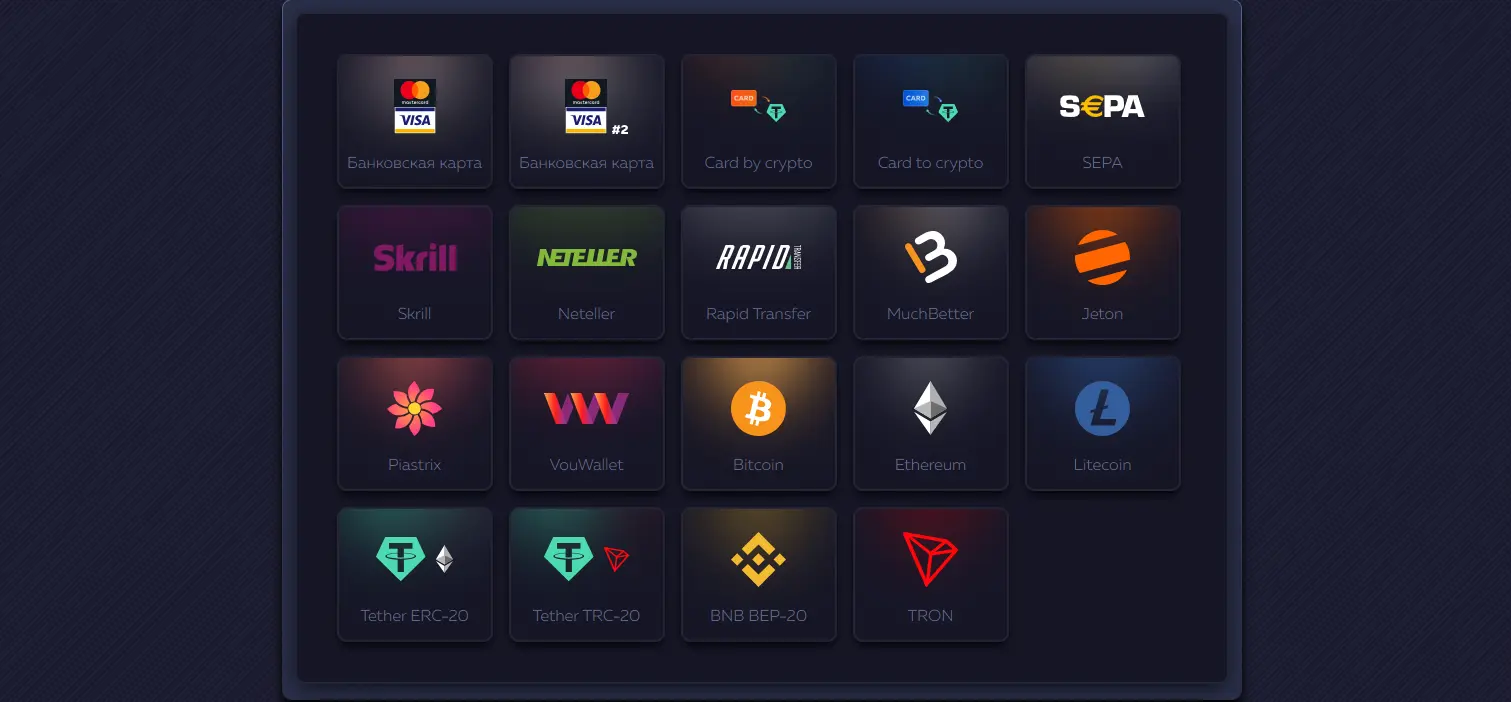

Финансовый раздел проработан до мелких деталей. Транзакции обрабатываются в течение 24 часов без вычета каких-либо комиссий. Казино Вавада поддерживает 20 фиатных валют и принимает 6 видов криптовалют:

- RUB;

- ETH;

- EUR;

- PLN;

- BTC;

- USD;

- JPY.

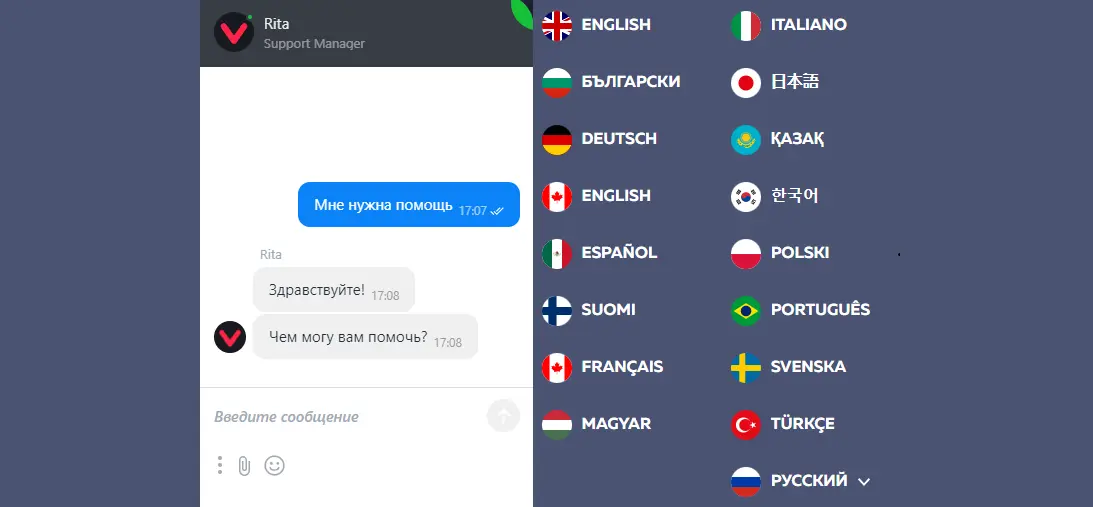

Сайт переведен на 19 языков, а поддержка работает круглосуточно. Связь со специалистами актуальна через живой чат и электронную почту. Бренд обладает лицензией Кюрасао, поэтому соответствует всем его стандартам. Для гемблеров, не способных контролировать и ограничивать себя во время игры, создан раздел “ответственная игра”. В нем представлены рекомендации по борьбе с зависимостью. Защита персональной информации и денежных средств обеспечивается системой шифрования. Дополнительно через личный кабинет Vavada можно подключить двухэтапную аутентификацию. При подозрительной активности представители компании оставляют за собой право потребовать подтверждение личности.

Бренд Вавада Казино легален в более 45 государствах: включая страны СНГ, Европы и пр. Но правительства отдельных государств не поддерживают азартные развлечения на территории своих стран. Поэтому посещение площадки в таких государствах запрещено. Чтобы попасть на платформу придется использовать рабочие зеркала.

Зеркало Вавада

Зеркало это копия сайта, которая позволяет юзерам попасть на портал в обход всех ограничений. Такая платформа работает на другом прокси-сервере. Это дает ей возможность скрыть от интернет-провайдеров свою деятельность на территории запрещенной страны. По функционалу, дизайну и предложениям оф. сайт и сервисы-копии полностью аналогичны друг другу. Разница заключается только в ссылках: в адресах зеркал Vavada часто встречаются доп. символы, буквы или цифры. Кроме того, альтернативные клубы работают недолго (20-30 дней), ведь РКН вынуждает провайдеров выявлять такие площадки и блокировать их.

Чтобы всегда оставаться в игре, нужно знать несколько способов поиска таких альтернатив:

- запросить ссылку на актуальное зеркало Вавада у службы поддержки;

- самостоятельно изучить поисковые выдачи;

- почитать информацию на форумах;

- ознакомиться с рекламными материалами, представленными партнерами ресурса.

Первый вариант самый безопасный, ведь сотрудники платформы предоставляют только официальные рабочие зеркала Vavada. Так клиенты не столкнутся с мошенничеством, а их деньги и персональные данные останутся в безопасности. При этом для игры нет необходимости создавать новый аккаунт - два сервиса работают с одной базой данных, а все настройки и информация дублируются между ними. Если учетной записи нет, то процедура создания профиля соответствует той, что используется на оригинальном портале.

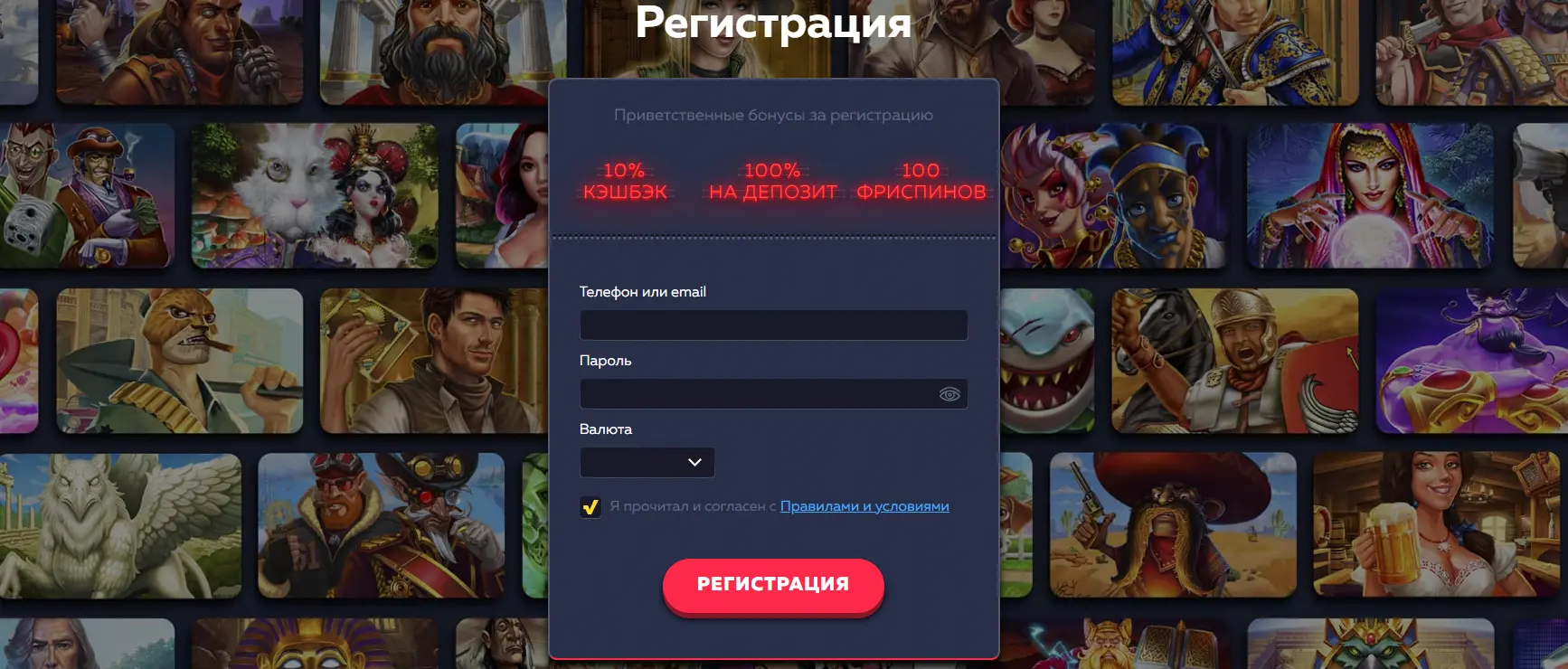

Создание аккаунта в Вавада: вход и Регистрация

Для игры в casino в бесплатном режиме не нужен аккаунт. Но, если цель гемблера развлечения на реальные деньги, то ему придется завести учетную запись. Для этого нужно выполнить несколько шагов:

- открыть официальный сайт;

- нажать “Регистрация Вавада”;

- вписать номер телефона или адрес email;

- задать пароль;

- выбрать одну из 19 валют;

- прочесть и согласиться с правилами и условиями;

- завершить процедуру.

Сразу после этого на бонусный счет придет 100 фриспинов для Great Pigsby Megaways. Чтобы участвовать в других акциях и полноценно пользоваться платформой, нужно подтвердить аккаунт. Для этого следует перейти по ссылке из письма, если регистрация проходила через эл. почту . При создании профиля через телефон потребуется указать код из СМС. Для его получения нужно открыть вкладку “Профиль” и нажать “Получить код”. Затем указать шифр в соответствующем поле.

Верификация в Vavada online не обязательна, но при выводе крупных сумм или подозрительной активности представители казино вправе запросить подтверждение личности. Поэтому рекомендуется сделать это заранее. Для прохождения KYC достаточно отправить администрации фото документа, подтверждающего личность: водительских прав, паспорта, удостоверения личности. Проверка длится не более суток, а по ее завершении можно полноценно пользоваться заведением: вносить депы, выводить выигрыши, активировать промо.

Акции Vavada

Для поощрения пользователей у заведения есть награды за регистрацию, активность, использование промокодов Вавада. Все акции размещены в блоке “Бонусы” во вкладке “Профиль”. Там же указаны критерии для получения поощрений и требования по их отыгрышу. Каждый клиент вправе отказаться от любого предложения, нажав кнопку “Удалить”.

Приветственный подарок за регистрацию

За регистрацию новички получают порцию приветственных фриспинов Вавада. Они начисляются сразу после заполнения регистрационной формы. Потратить 100 бесплатных вращений разрешено в автомате Great Pigsby Megaways от бренда Relax Gaming. Вейджер для отыгрыша составляет х20, а на его выполнение отведено 14 дней.

Дополнительно предусмотрен 100% фрибет. Получить его и перевести в реальные деньги можно после выполнения некоторых условий:

- внести на баланс от ₽50;

- выполнить 35-кратных вейджер;

- проставить активы в категории “Слоты”;

- отыграть их в течение 2 недель.

Максимальный размер free bets составляет 90 000 рублей, а потенциальный приз не должен превышать х10 от полученных бонусных средств. Так при пополнении счета на 2000 RUB, пользователь получает на баланс дополнительные 2000 рублей фрибета. Максимально возможный заработок с них ₽20 000.

Промокоды Vavada

Специальные коды позволяют юзерам получать на свой счет дополнительные фриспины и фрибеты. Количество поощрений зависит от типа промокода. Найти promo codes можно в социальных сетях заведения и рекламных предложениях компаний-партнеров. Активируются промокоды в разделе “Бонусы”. Для этого нужно вписать код в отдельный блок и нажать “Применить” активы зачислятся на счет.

Кэшбек

Активно вращая автоматы в течение месяца, гемблеры могут претендовать на cashback в размере 10% от потраченных денег. Так, если участник за месяц потратил больше денег, чем заработал, клуб возместит ему 10%. Если условия не выполнены, то кэшбек не начисляется, но юзер может претендовать на подарок в следующем месяце. Отыгрыш для акции х5.

Loyalty program

Для мотивации и поощрения постоянных пользователей онлайн казино Вавада предусмотрело многоуровневую Vip-программу. Программа лояльности включает 6 уровней: Новичок, Игрок, Бронзовый, Серебряный, Золотой, Платиновый. Первый статус выдается сразу после регистрации. Остальные звания присваиваются исходя из объема ставок за месяц (в долларах):

- Новичок 0;

- Игрок 15;

- Бронзовый 250;

- Серебряный 4000;

- Золотой 8000;

- Платиновый 50 000.

Достижение любого статуса дает участнику определенные поощрения. Из основных привилегий: расширение перечня доступных турниров, увеличение лимитов на cash-out, предоставление персонального сотрудника техподдержки. Каждый месяц статусы обновляются, исходя из активности участников.

Все награды выдаются в компьютерной и мобильной версиях заведения, а также в приложениях.

Мобильная версия Vavada и симулятор

Чтобы удовлетворить потребности всех посетителей, площадка адаптировала сайт под смартфоны. Для входа в заведение через мобильное устройство не нужна установка дополнительного софта: гемблер открывает площадку через любой браузер, вводит данные от аккаунта и начинает игру. Все функции и дизайн не отличаются в версиях для ПК и смартфонов. В мобильном казино актуальны те же разделы, функциональные блоки, кнопки, бонусы, автоматы. Разница заключается только в объединении вкладок “Пополнить”, “Помощь”, “Профиль” в один блок, а также адаптации площадки под вертикальное расположение экрана.

Дополнительно ресурс выпустил отдельное приложение. Для его использования подходят все устройства с версиями операционных систем Android, Windows и iOS. Чтобы играть через гаджет, предварительно необходимо скачать Вавада на телефон:

- перейти в casino и связаться с СП;

- запросить ссылку на приложение, указав ОС гаджета;

- скачать клиент;

- открыть загруженный файл;

- через “настройки” разрешить установку из неизвестных источников;

- открыть симулятор и войти в профиль.

Внешне у приложения и мобильной версии нет никаких отличий. Разница между ними состоит в функциональных особенностях. Например, симулятор лучше адаптирует входящий интернет-трафик по сравнению с мобильной версией, поэтому площадка работает более стабильно. Приложение Vavada взаимодействует с системными программами смартфона, так что игрок всегда может своевременно получать уведомления об акциях клуба и важных обновлениях. К тому же приложение всегда остается под рукой и не нужно постоянно входить в учетную запись. Так получить доступ к слотам становится еще проще и быстрее.

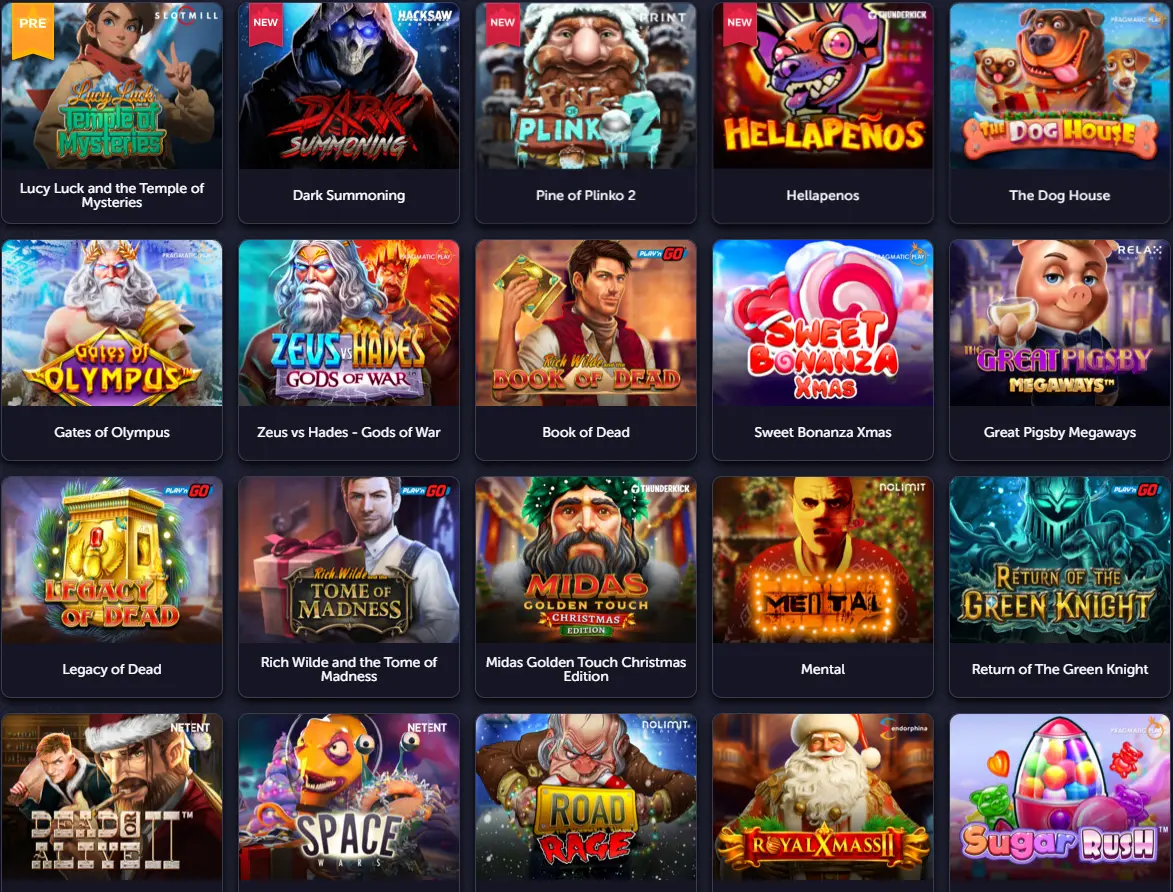

Игровые автоматы Вавада

Весь софт, а это 5000+ релизов, создан 42 провайдерами: NetEnt, IgroSoft, PlayTech, Red Tiger, QuickSpin, Microgaming. Все автоматы поделены на категории: “Столы”, “Лайв”, “Слоты”. Большинство из них оснащено бесплатным режимом. В живом казино все желающие могут понаблюдать за происходящим, изучить функционал и правила. Розыгрыши проводятся с использованием ГСЧ, поэтому все выигрыши в аппаратах случайны. Каждая ставка вне зависимости от ее размера имеет равные шансы на выпадение джекпота. Сейчас клуб разыгрывает три главных приза Mega (почти 500 000 долларов), Major ($15300), Minor (2000 USD).

В категории “Слоты” представлено 4500+ релизов. Среди них гемблеры обнаружат нестареющую классику, фруктовые и трехбарабанные машины, видео и 3D аппараты, современные релизы, Megaways, прогрессивные автоматы и другие предложения. Среди популярных тем: динозавры, Боги, древность, сладости, культуры, фильмы. Вот несколько топ игр Вавады:

- The Dog House;

- Gates of Olympus 1000;

- Sweet Bonanza;

- Most Wanted;

- Ice Princess;

- Big Bass Floats My Boat;

- Cleocatra.

В разделе “Столы” посетителям предлагается около 80 развлечений. Среди них есть карточные, аркадные, краш и настольные игры Vavada. Самые популярные релизы: Авиатор, Блэкджек, Покер, Минер, Рулетка. Категория “Live” огромна: 120+ наименований аппаратов от 4 провайдеров. В ней размещены не только карточные и настольные развлечения, но и редкие наименования: Sweet Bonanza Candyland, Sic Bo и прочие.

Техническая поддержка

Поддержка компании функционирует без выходных, 365 дней в году. Сотрудники владеют двумя языками: английским и русским. Обращения принимаются через лайв-чат (срочные запросы) и электронную почту (проблемы, требующие более детального рассмотрения). Через живой чат время ожидания составляет до 10 минут, а вот на заявки, оставленные через email, менеджеры техподдержки Вавада отвечают в течение 24 часов.

Через СП все желающие могут подать заявку на подключение к партнерской программе.

Партнерская программа

Партнерская программа клуба функционирует по трем моделям: RevShare, Hybrid, CPA. В первом случае условия фиксированы: brand выплачивает до 50% от депозитов аффилиатов. По второй модели условия обсуждаются индивидуально с каждым арбитражником. Третья модель подразумевает разовую выплату в размере до 300 USD за каждого привлеченного реферала. Сумма определяется менеджером компании индивидуально, исходя из трафика партнера. Подтверждение трафика занимает до 30 дней. Одно из условий affiliate program не учитывается трафик из ряда стран:

- Великобритании;

- Ирана;

- Германии;

- Индии;

- Грузии;

- И др.

Чтобы присоединиться к affiliate program от Vavada casino, следует отправить запрос в техподдержку. После одобрения заявки в личном кабинете появится специальная вкладка, за партнером закрепляется affiliate-менеджер, бренд предоставляет собственные рекламные материалы. Выплаты осуществляются дважды в месяц (1 и 15 числа). Заказать кэшаут можно при сумме 1000+ RUB.

Способы пополнения и вывода средств

Заведение поддерживает работу 32 платежных сервисов, принимая 20 валютных единиц. Совершить транзакции предлагается с помощью банковских карт, криптовалют, эл. кошельков и различных переводов. Все финансовые операции осуществляются через раздел “Кошелек”, в котором есть вкладка “Пополнить”, “Вывести”, “Перевести”, “История”. Здесь же предусмотрен блок, где можно изменить валюту игрового счета.

Лимиты по депозитам в оф. Vavada фиксированы: минимальная сумма 50 RUB, максимальный деп не установлен платформой, но ограничен используемой платежной системой. Ограничения по кэшауту следующие: принимаются заявки от ₽1000 до 1 миллиона рублей за раз. Но максимальная сумма транзакции зависит от статуса игрока в Loyalty Program:

- для “Новичка” и “Игрока” 1000$ в сутки;

- для “Бронзового” 1500 USD;

- для “Серебряного” 2000 долларов США;

- для “Золотого” $5000;

- для “Платинового” до 10 тысяч долларов США.

В праздничные и выходные дни для всех членов ресурса ограничения одинаковы: вывод с Вавада не должен превышать 2000 USD в течение дня.

Сроки проведения операций зависят от выбранной платежки. Так при пополнении баланса через крипту время ожидания не превышает 2 часов, а через другие варианты до 5 ч. Скорость кэшаута также определяется вариантом платежного сервиса: с помощью цифровых активов вывод осуществляется в течение 6 часов, а через другие методы до 24 ч. Казино не взимает комиссий.